I love words – their power to conjure up vivid images and trigger emotional responses. As a writer, words are the tools of my trade. Sometimes I use them successfully, at other times the right word can float tantalisingly just out of grasp.

But I’m increasingly aware that I’ve allowed my perceptions of one particular situation to be distorted by words. I’m talking about the crisis in Europe. The one encapsulated by the heart-breaking photos of a little boy's body being carried off a Turkish beach.

But what to call this crisis? Are the people at the sharp end ‘migrants’ or are they ‘refugees’?

A quick survey of today’s front pages shows an almost 50/50 split. Meanwhile, Radio 4 this morning used ‘migrant refugee situation.’

Words have never seemed to matter more. Because depending which one is used makes a vital difference to how we perceive the situation. It certainly has for me.

According to a dictionary, ‘migrant’ is – should be – a neutral word. It’s no more or less than someone who goes from one country or place to another.

But to me ‘migrant’ suggests a plucky go-getter, someone who simply wants to improve their standard of living. Someone who has made a rational choice about moving to a new country, filled in the forms, booked their plane ticket, is taking their own chances.

Meanwhile, ‘refugee’ implies desperation – a person who has no choice but to flee an inhumane situation, usually conflict. To be a refugee, according to the 1951 Refugee Convention, requires fulfilling specific criteria that you have a well-founded fear of persecution.

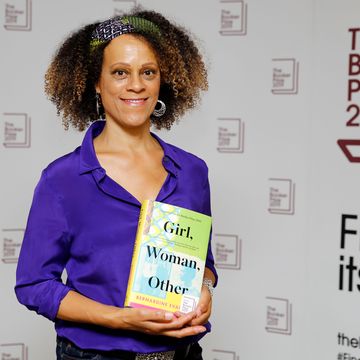

All photos Getty

The issue of people drowning in the Mediterranean after crowding onto leaky rust-buckets to sail to Europe isn’t new. People camped out in huge numbers in dreadful conditions at Calais or trekking across Europe isn’t either.

But for a long time I was able to push the deaths, the desperation, to the back of my mind because of the word ‘migrant’, feeling that if someone has made the choice to move to a different country then they alone are responsible for the risks they’re taking.

It’s not a response I’m proud of, though I’m sure I’m not alone. I think the ‘m' word has delayed the humanitarian response these people desperately deserve and enables some governments to keep the issue well down their to-do lists or even profit politically.

Of course, what’s really at stake is how to solve the bigger problem, one that’s so vast and complex that the European leaders have no idea how to tackle it, let alone me.

But what I do know is that hiding behind words isn’t right, and distracts from the issue. Because no matter whether you’re a ‘migrant’ or a ‘refugee’, you’re still a person – somebody’s son or daughter, a wife, a husband, a mother, a father. Often you’re a child.

Surely anyone who feels life in their country is so unbearable that they are willing to risk life and limb to escape it, risks their child’s life too, hasn’t got a ‘choice’ and deserves our humanity?

Oh yes, and the little boy’s name was Aylan Kurdi. He was three.